How Children Learn to Read

The road to reading is a long, complex journey that begins in infancy. Learning to competently read, write, and spell requires a rich background of literacy-related experiences.

When nurtured and given these experiences, research tells us virtually all students can learn how to read. Only 1-6% of students have such severe learning disabilities that they may always struggle to read. As mentioned, the current model of reading instruction in a majority of US schools only works for some students. I am interested in helping ALL students become skilled readers.

When we know better, we can do better, so let’s discuss how the brain actually learns how to read.

WE DO NOT LEARN TO READ NATURALLY

Brain research tells us humans do not learn to read naturally. Speaking is natural, but reading and writing are not. These skills must be taught and explicit, systematic instruction has the greatest outcome for success.

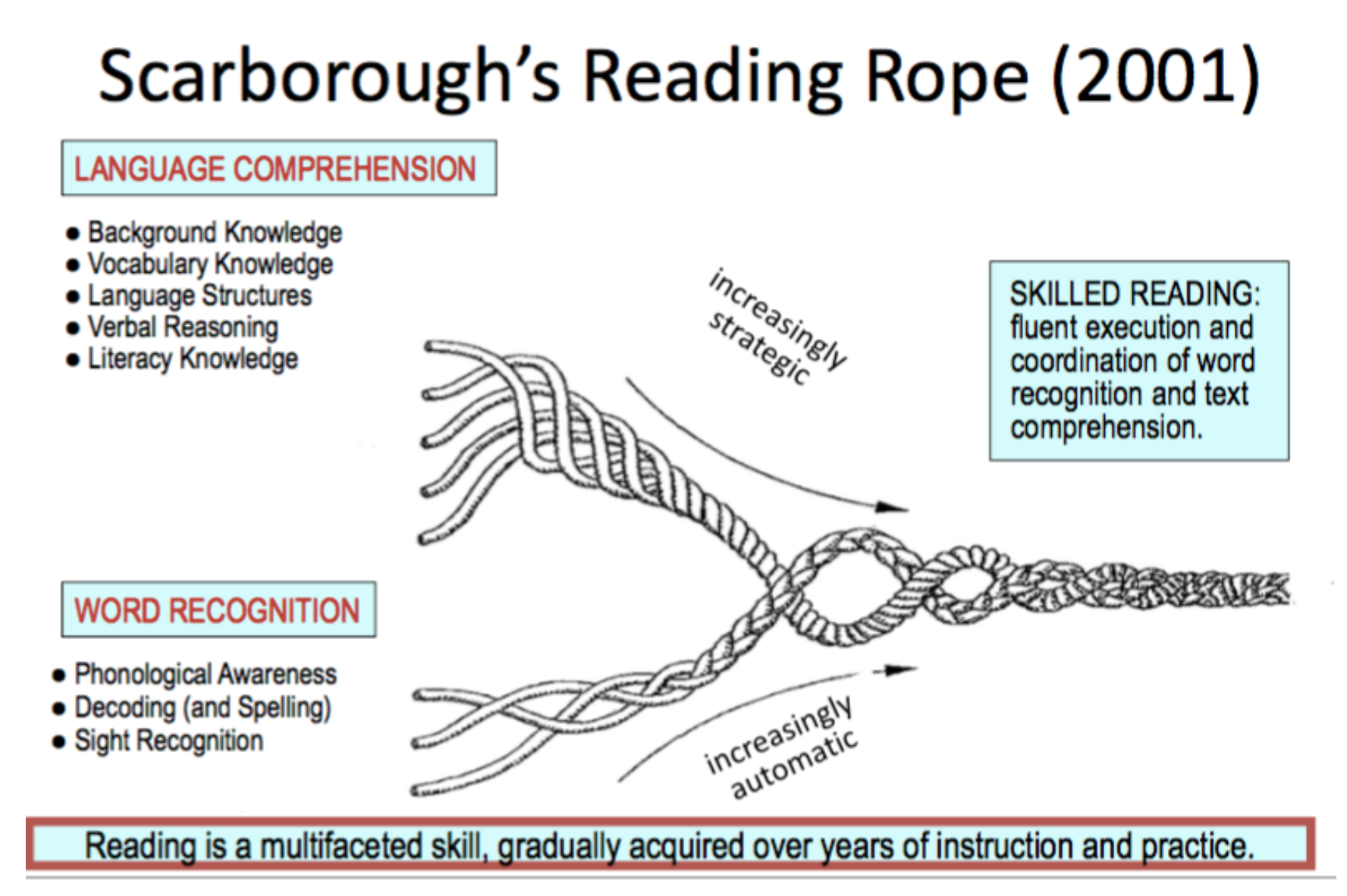

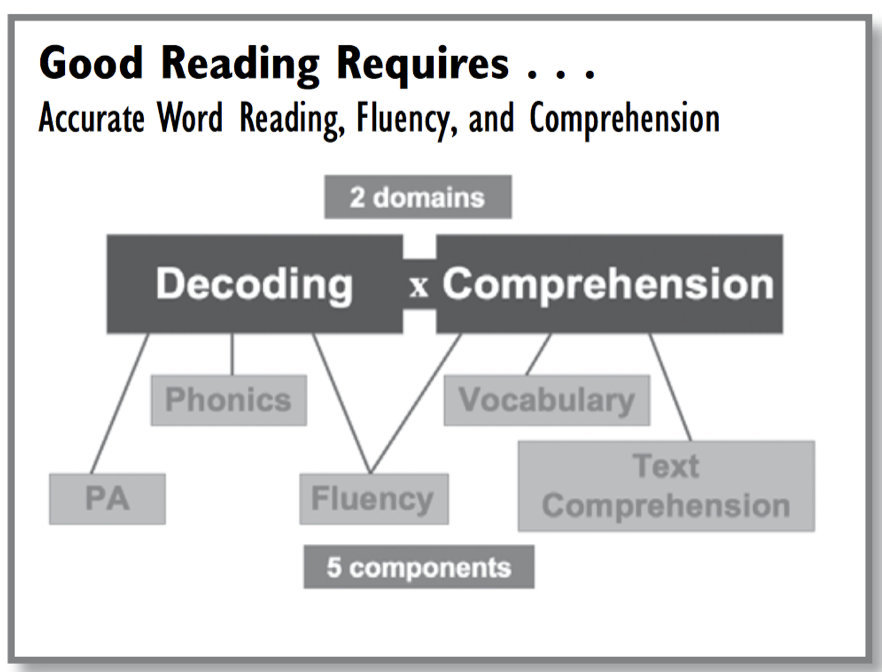

Writing is a code humans invented to represent speech sounds. A reader’s job is to “crack this code” and figure out how the words he/she hears and knows how to say connect to the words on the page. This is actually a very complex process. Consider all of the skills required to truly understand what we are reading:

There are four main areas of the brain that must work together during reading:

The context processor, which deals with background information and sentence context

The meaning processor, which deals with vocabulary and meaningful word parts (morphemes)

The phonological processor, which deals with speech sounds

The orthographic processor, which deals with letters and spelling patterns

EYE MOVEMENT: LETTER BY LETTER

Many years ago there was a big movement for whole language and it was believed that proficient readers could skip words, use context to process words, or bypass phonics. While it may seem like that happens for skilled, avid readers, eye movement studies have shown that simply isn’t true. Our eyes chat with our orthographic and phonological processing systems within milliseconds!

Reading is accomplished with letter-by-letter processing of the word. Fluent readers perceive EACH and EVERY letter of print. Thus, we can distinguish beach from bench, grill from girl, and primeval from prime evil.

Skilled readers process the internal details of printed words and match them to the individual speech sounds that make up the spoken word. Even when "chunks" are recognized, they can be analyzed into their individual sound-letter correspondences on demand (within milliseconds).

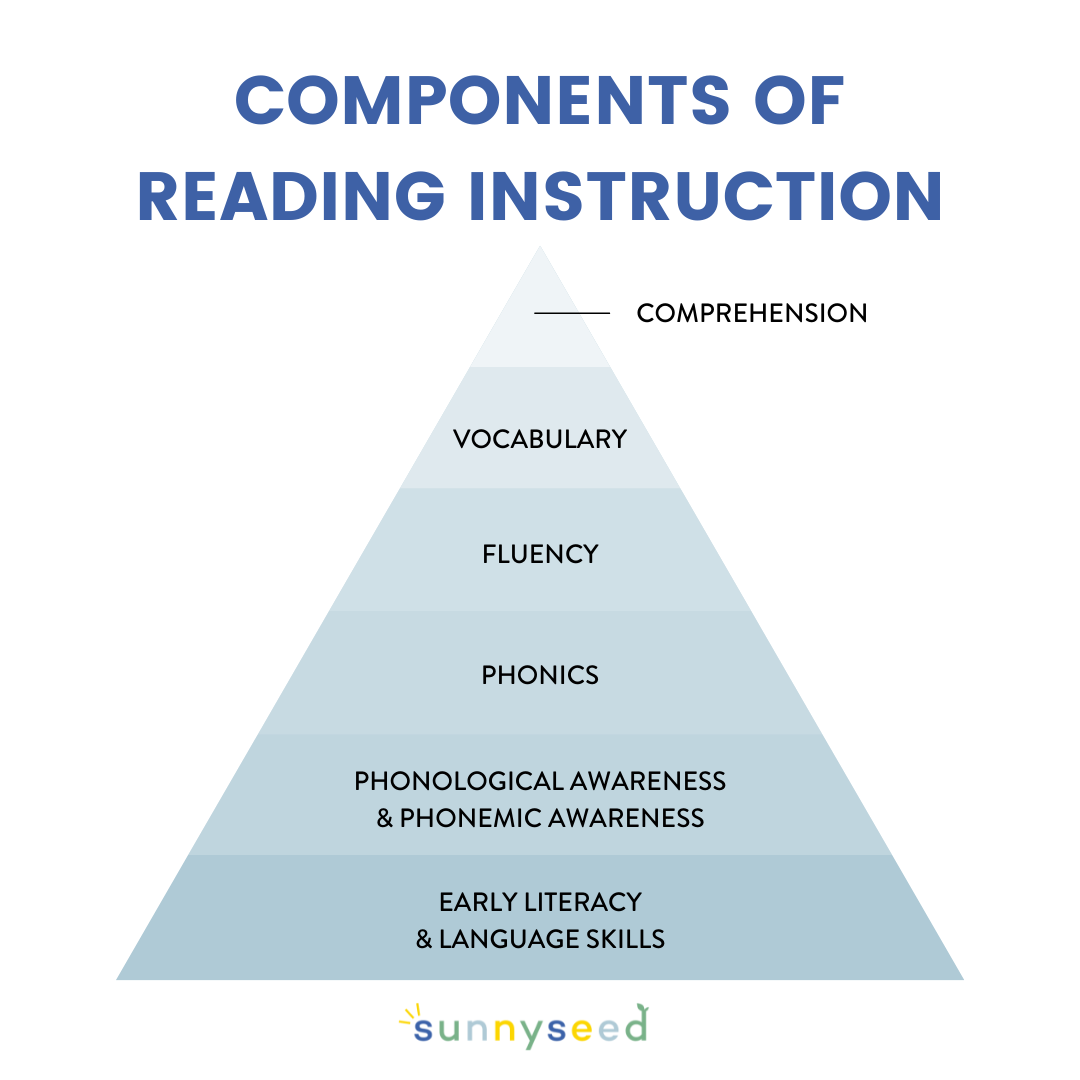

COMPONENTS OF READING INSTRUCTION

Taking all of this into consideration, experts have agreed there are six primary components of literacy instruction. This has even been recognized and published by the US Government during the National Reading Panel in 2000, yet this is not the framework used in many elementary schools.

LETRS Foundation

STAGES OF READING DEVELOPMENT

Prealphabetic reading - The child does not know that letters are used to represent speech sounds and cannot identify the separate speech sounds.

Partial alphabetic reading and spelling - The child tries to use letter names to figure out the sounds and represents some of the sounds in a word. The child needs better phoneme awareness and more knowledge of conventional spelling.

Full alphabetic reading and writing - The child has good phoneme awareness, knows most basic sound/symbol correspondences, can spell phonetically, and tries to sound words out. This is typically achieved by first graders.

Consolidated alphabetic reading - The child has a substantial sight vocabulary, uses several strategies to recognize unknown words, and tries to spell the meaningful parts of words. The recognition of words is mostly automatic and attention is devoted primarily to comprehension at all levels. This child is able to spend less attention on sounding out words letter by letter and can read words by analogy to known words. Children in this stage greatly benefit from reading series of books at their appropriate reading level. This builds their fluency.

SLOW DOWN

Children cannot be hurried because learning to read is one of the most challenging perceptual and cognitive tasks in early childhood.

Learning to competently read, write, and spell requires a rich background of literacy-related experiences.

“There is no evidence globally to suggest reading at age five leads to greater academic success.” - Reading Instruction in Kindergarten: Little to Gain and Much to Lose (Alliance for Childhood; Defending the Early Years, 2015)